Superintendent HD Chambers took off his glasses and rubbed the bridge of his nose. He looked up at the camera and spoke; his voice wavering from merely mentioning teachers.

“I just wish there was a mechanism that was clear and definitive,” Chambers said, “in terms of recognizing and appreciating what teachers have been going through, and what they’ve been doing for kids.”

The abrupt change caused by COVID-19 in March 2020 was difficult for teachers all over the district.

“We were beginning to have… a lot of staff members voice concerns with the unknown, because… we weren’t sure how it was transmitted… [or] the impact of students being asymptomatic,” Chambers said, “So I made the decision on the afternoon of March 11th, to cancel school [March 12th].”

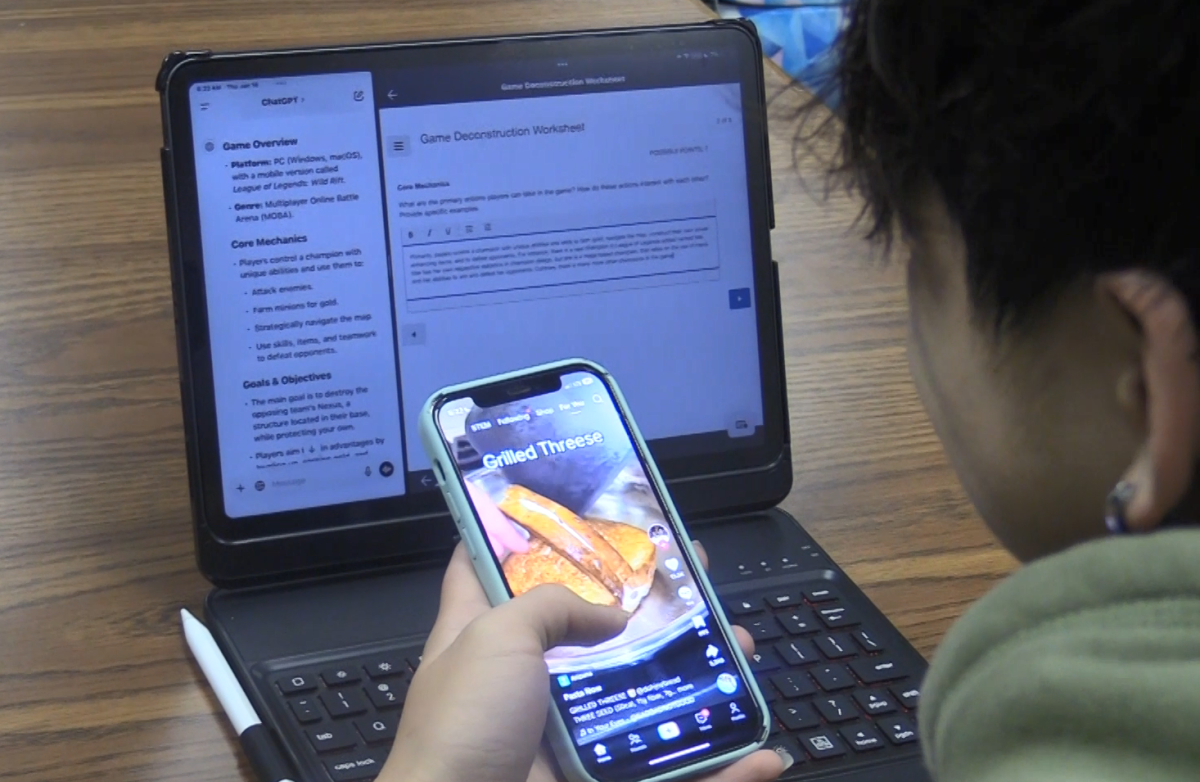

By summer, it was evident that the virus wasn’t going to subside. It was then decided that school in 2020-21 would temporarily be virtual until the virus subsided.

“I was optimistic that we had done as much as we possibly could do to prepare the staff in the spring and in the summer to open up in a virtual environment,” Chambers said.

In just a few short months, Alief prepared all of its staff to manage and teach to accommodate online learning.

“[Teachers] have literally taken 150 years of educational theory and flipped it on its head in about three months, and started teaching school in a completely 180-degree different way,” Chambers said.

Chambers has a plan set in place to reach out to parents and students about the shift from online learning to in-person.

“So we’ve got a massive marketing plan, a campaign if you will… going on right now,” Chambers said, “We also have addresses of families that have not shown up and teams of people going out knocking on their doors, just trying to make a personal connection with them and say, ‘Listen, you know, we’re open, we want your child in school.'”

Chambers has three goals for the district following this pandemic. The first goal being more focused on teachers.

“People tell me all the time, ‘I don’t want your job as superintendent. I’d hate to have your job…’ And it’s true, I’ve got my own responsibilities, but nothing like a classroom teacher.”

“We’re working on a statewide program that we call the teacher incentive allotment. It is a way for us to recognize the truly great teachers based on real evidence… and financially reward them at a greater level than what they’re being paid right now,” Chambers said, “So we’re still moving forward with that [but] it’s just been kind of slowed down… because of COVID.”

The second goal for Alief is something that affects students.

“We are looking at a very pilot elementary school, that we can kind of extend the school year, so that kids are not missing as many days during the summer break as they are right now. It’s called additional school days,” Chambers said.

He explains in depth how it’ll work and how it isn’t much different from this school year.

“For this type of pilot, you’d have a break in the fall, you’d have a break… [for] Thanksgiving and Christmas, you’d also have another little break in February, then you’d have a spring break. The school year would start earlier and it would run through probably the middle of June, into June,” Chambers said.

His intentions for extending school are simple: to promote a better learning environment. The two and a half month gap between one grade to the next can be detrimental to students.

“…the way in which we have school calendars now, our most vulnerable little students are pre-k kids, our first, second, and third graders, our non-English speaking kids, our undocumented children, and our… [students] that come from an educationally deprived family,” Chambers explains.

His last goal is to increase the number of students that are college, career, or military ready. For now, he is focused on reenrolling children back into in-person learning.

“As we’re phasing in these openings, some families are still worried concerned about about their their young child going to school because of because of covid. So there’s a lot of parents, a lot of families of four-and five-year-olds, who just don’t have their children in school right now… It’s not a Houston problem, it’s an everywhere problem.”