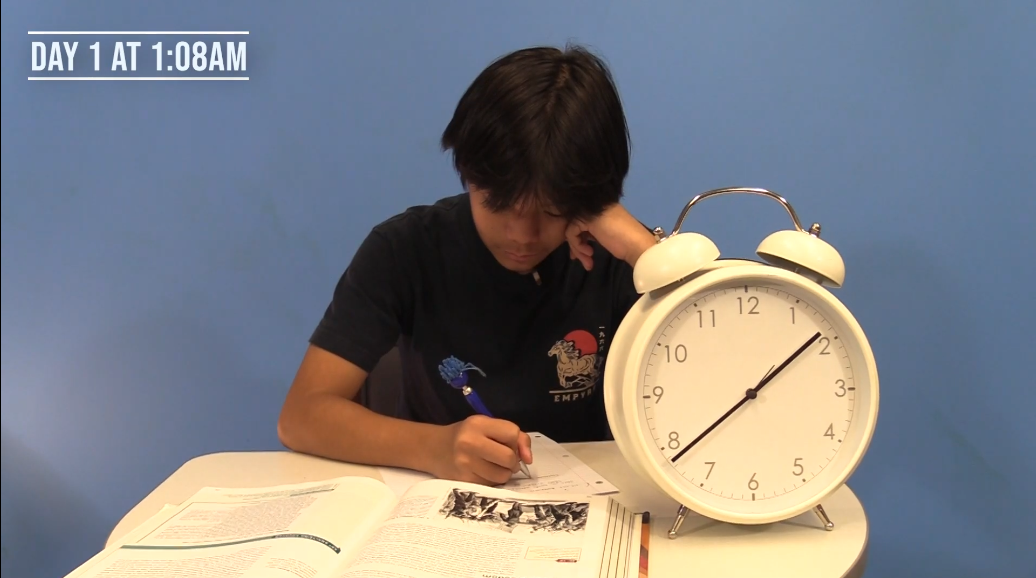

Twelve-year-old Nimra Ahad was sitting at her bedroom desk doing homework on an evening much like any other when she nearly died.

“I was gasping for air and it wouldn’t come,” Ahad said, recalling the frightening event that took place during the cold winter in her hometown of New York City. “I felt like my breathing stopped and…I thought that I was going to die.”

Ahad, now a junior, had suffered through a serious asthma attack on that unforgettable evening. Ahad has chronic asthma and, much like the other 25 million Americans that suffer from the serious lung disease, lives a life fringed daily with the frightening possibility that at any second a life-threatening attack can occur. Those afflicted with the disease must take special precautions, medications, and care, sometimes completely changing their lifestyle to avoid serious episodes like Ahad’s. From simply practicing a few basic breathing exercises each day to having to move to completely different state, those life changes can range from rudimentary to the extreme.

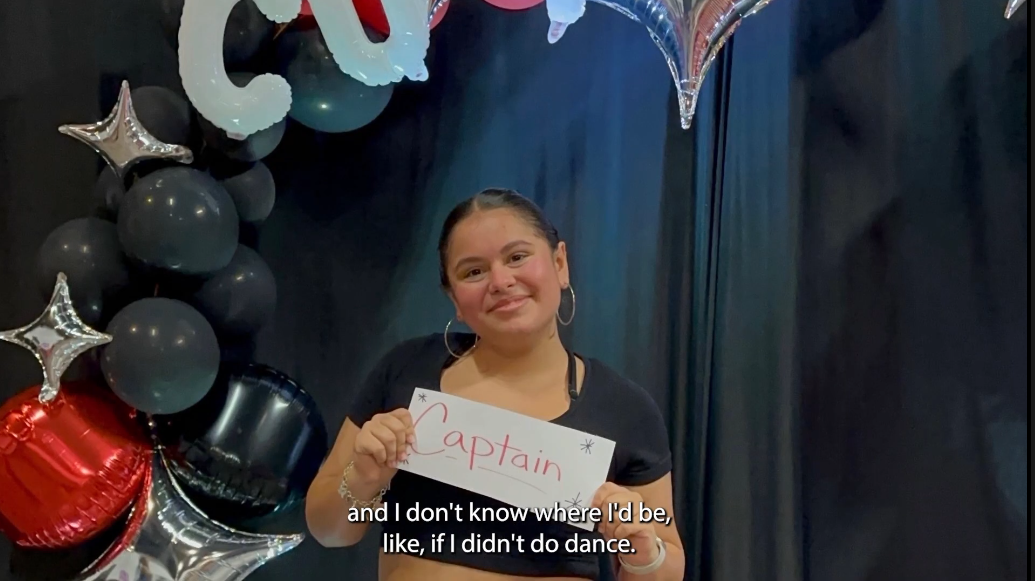

For senior Rosie Tran, asthma was the reason why she moved to Houston from her home state of Washington.

“I almost died like two or three times,” Tran said. “I would just stare at my mom and I just looked dead so she had to take me to the hospital. It got to the point where it kept happening and my mom was like ‘You know what, I don’t want to put your life in danger anymore’ so she decided to tell my family to move to a hotter state.”

Tran’s family packed up their bags, first moving to Florida, then, after a month, to Houston.

“And that’s how I came here,” Tran said. “So if it wasn’t for asthma, I would still be living in Spokane, Washington.”

In the same way, Ahad, originally from New York City, moved to Houston because her family had decided that it was the best decision for her health.

“After [the attack] we actually moved to Texas because the weather from New York was too severe for me,” Ahad said.

Ahad’s family had made the decision to move because they put their daughter’s health over the inconvenience of starting a new life elsewhere.

“I definitely appreciate [my parents’] concern…and for making that big of a decision,” said Ahad. “I really did like New York but you know if I had to choose my health over an environment I would choose my health. If I compare the number of absences I’ve had in New York to those in Texas it would be significantly different because I’m sick a lot less…which definitely makes a difference.”

Aside from having had to move to a safer climatic environment, both Tran and Ahad had to continue to take precautions even in their new, more tolerable conditions.

“Sometimes when I feel like I can’t breathe, or I can’t catch my breath, I use my inhaler,” Tran said. “Or like right before I sleep every night I have to use my inhaler or else I cough a lot or I can’t breathe when I sleep.”

But not all cases are the same. Ahad’s asthma remains dormant for the most part of the year but can surface and flare up if triggered by certain environmental conditions.

“There’s not necessarily [a routine] but usually in the Spring season I take my inhaler twice a week,” Ahad said. “It just surfaces up whenever there are allergy seasons or whenever it gets triggered. So it’s really difficult for me to take in pollution. But if I take proper care, which is not going into hazardous environments and that sort of thing then it can stay dormant.”

In Ahad’s case, her asthma was a bit easier to control and she was even able to train her body over time to function with less medication.

Senior Navoda Perikala actually uses two different medications for her condition, depending on the severity of the situation.

“I’m supposed to take my inhaler every day but I don’t [unless] I can tell that it’s getting worse, then I’ll take it,” Perikala said. “There’s one that’s mostly a preventative thing and then the other is for if [an attack] happens.”

According to school nurse Carol Wiley, this routine can change if an attack happens during school hours.

“Here at school if they need their inhaler at any time, for all medications of course, I need to have a physician’s order and the inhalers need to be kept here in the clinic,” Wiley said. “Unless there is an Asthma Action Plan.”

According to Wiley, only if the student has an AAP developed by a doctor is the student allowed to use their inhaler on their own in the classroom.

“[With the AAP], the doctor has stated the student understands their disease process well enough and can keep his inhaler or her inhaler on their person so they would use their inhaler in the classroom,” Wiley said. “Now if after they use the inhaler, it’s still not helping them and opening them up, then they need to come see me so that I can go ahead and I can listen to their lung fields to see how much air is getting in and out and see if there’s something else that I can do.”

Despite having to go to great lengths to keep their asthma in check and under control, Ahad, Perikala, and Tran never feel that their condition makes them any different from their peers or prevents them from enjoying life in the way that they want.

“I don’t feel like my life is any different, I mean if you count not going over 40 on the pacer test then that’s a disadvantage,” Ahad laughs. “So it’s very minor. I’m content with my life. I guess the fact that I can’t do certain things has always been there but it hasn’t made much of a difference.”

Perikala sees her life with asthma in a similar light.

“I don’t ever feel like my asthma limits me,” Perikala said. “I can pretty much do anything that anyone else can do.”

In fact, Perikala took up a challenge that most people might not expect an asthma sufferer to be able to do.

“I’m in band and like band actually strengthens your lungs so it helps if you play an instrument,” Perikala said. “I play the saxophone. I do have to work harder to have the same air support but [my asthma] doesn’t keep me from doing it.”

For many of the millions of Americans who suffer from asthma, their condition is not something that limits or restricts their abilities to live a normal life and is in no way considered by them an excuse to do less than what they know they are capable of. Instead, they see their condition as something to appreciate and maybe even be thankful for knowing how much worse other illnesses can be.

“Asthma is not a disability,” Ahad said. “I think there are other things that are much worse. It’s just one of those conditions that you learn to live with but I’m glad I have it better than many others.”